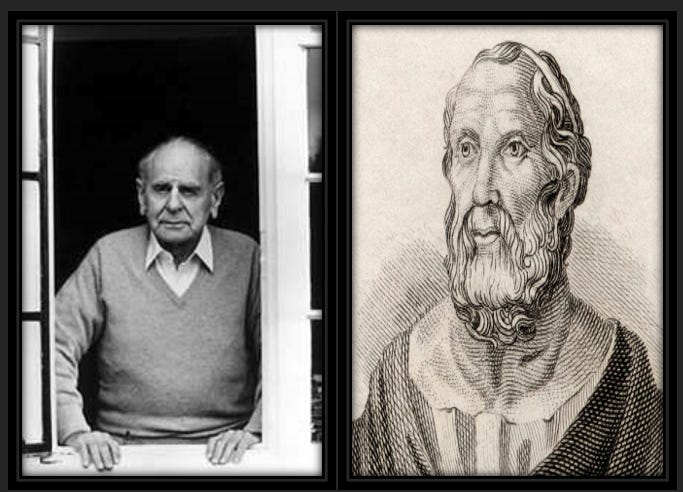

Karl Popper Takes on Plato

Platonic philosophy as the ancient origins of anti-democratic totalitarianism

It has been several years since I’ve read Plato’s Republic. My main takeaway of it as I attempt to recall it from the dim and clouded lens of my memory is that a society could be brought to a more ideal state if they are led by a highly educated and virtuous set of citizens and in turn, the citizenry itself was wise and virtuous to know how to follow and further assist and enable such enlightened rulers. I also recall being drawn to and appreciating his allegory of the cave. Although I was in a much more dogmatic libertarian phase of my life at the time of reading it, I don’t recall having a particular fearful reaction to Republic as much as thinking that there was a lot of good aspirational philosophy in it, albeit some of it was too utopic and unrealistic to fully realize on earth.

Not so fast, says Karl Popper in the early sections of his work The Open Society and Its Enemies, which I’ve recently started reading. Plato’s philosophy isn’t so benign and is the foundation of many closed and anti-democratic ideologies, from fascism to communism.

According to Popper, at its core, Plato’s philosophy could be summed up as a belief that moral decay occurred because of political and societal decay, and that this process of decay could be stopped insofar as every earthly thing that decays has a corresponding perfect thing, a form or an idea that exists beyond time and space that does not and cannot change. The task of man, or rather the enlightened leaders of man, was to build up knowledge so as to understand those perfect forms and ideas. The impetus for Plato’s search for the ideal political state was that he was greatly troubled by the main thrust of Grecian philosophy that predated him, dominated by the philosophy of Hericlitian, in which the world was thought to be in constant flux and decay. To unwind and reverse this dystopic vision, Plato followed the thread backwards: if things are in a constant state of flux and decay since the origin of the world, then one can follow the arc of history backwards to discover the perfect ideal forms that existed before humanity. If humanity is an imperfect copy of the gods, and gods represented specific elements of perfected virtues, then man can define those perfected forms through what they knew about the gods, rigorously train people on them, and select the leaders who represent them the best to lead them.

Or, as Popper states it:

Plato wanted to unveil the secret of decay and flux, of its violent changes, and of its unhappiness. He hoped to discover the means of its salvation. He wanted to bring the unchanging perfections of the space beyond to earth…Plato aimed at discovering the secret of the royal knowledge of politics, of the art of ruling men…”

I am too early into my reading of The Open Society and Its Enemies to see the directions Popper takes this, but I don’t think the implications of where he will go from here are too hard to predict. Such a philosophy assumes one can trace back the lineage of dystopia to the ideas and forms of utopia. Further, that such ideals that lead to a utopic state can be trained and enshrined into mankind, especially the most noble and enlightened of mankind, to arrest the process of chaos and decay. A belief that man could take hold of and leverage such a philosophy and achieve an ideal state (or race) when combined with what Popper defines as “social engineering” to change the nature of man is indeed the underlying philosophy that would surface in ultimately murderous ways on a staggering scale in utopic visions and realities of both fascism and communism in the 20th century.

And as Vasily Grossman in Life and Fate articulates through powerful prose, these totalitarian systems were more alike than their “enlightened leaders” would ever admit.